Not only did The 51st Open, held at Royal St George's, have the largest starting field ever for a Championship, but it was also the first edition to be played over four days. All that came before a 36-hole play-off, a concession for the title and a record-tying victory.

The starting field

Never before had an Open Championship been held over four days, but it became essential to do so in 1911 after a record field of 222 players started the Championship proper. There was no qualifying event, so all 226 accepted entries, before withdrawals, had to be accommodated.

And while The Open was starting to get used to big fields, with 210 entrants and 152 players starting the previous year, the Championship organisers were not familiar with fields so big.

The Sportsman suggested: "all those professionals who have any claim to compete in Championship events, and a very great number who possess none whatever, can be found in the list."

To cope, three sections of the draw were created, and it took three days for the field to play 36 holes, before the final two rounds were played all throughout Thursday. One section played on Monday morning and Tuesday afternoon, another played Monday afternoon and Wednesday morning and the third group played Tuesday morning and Wednesday afternoon.

No group appeared to have a distinct advantage, as two players from each section would go on to finish in the top six, but discord and controversy was still higher than The Open had possibly ever seen...

Controversy

In allowing so many players into the field, the Royal St George's committee were left with a tricky decision regarding pin positions for each of the days. But problems arose after their solution to the matter became apparent.

The players in the third section, beginning their first round on Tuesday morning, discovered that pins had been moved since the day prior, and as such were playing to different hole locations than the rest of the field did during their first round.

The committee had decided to change the pin locations at the start of each day, not after every round, and as such incurred a significant protest from the field.

The third section, playing to the new pins, were not overly unhappy as the pins seemed to be easier for them, but those who had completed their rounds the day before were not best pleased.

Allegations that the course had been made easier for the third section were made, and specifically a protest, echoed by players from every section, was organized against a violation of the spirit of the game, and the impossibility of an equal setup for all competitors.

James Braid, Captain of the PGA and at this point The Open's most prolific Champion, arranged for the protest on behalf of the professionals, but did not sign his name to it. A replay of the first day's play was offered by the professionals as a solution, and as Braid shot 78, speculation of his intentions were not what he desired to create. Willie Park Jnr, however, a two-time Champion Golfer, was one of a number of signatories of the document.

Yet the protest was not upheld, and the committee deemed their decision to cut new pins for each of the first three days appropriate in trying to accommodate the field size.

There was certainly no chance of a repeat controversy the following year. In 1912, qualifying was re-introduced, and remarkably, less players started The 52nd Open than made the cut in The 51st Open, with a field of just 62 compared to 1911's 222. The starting field size was cut by nearly 75%, and qualifying became more prominent in the Championship for decades, and even centuries, to come.

Thursday's excitement

As the controversy of the opening two rounds died down, Thursday's final 36 holes began with George Duncan possessing a considerable four-stroke lead, with a 144 total that included an astonishing front nine of 31 on Wednesday. But the 27-year-old had considerable star power right behind him.

In second place lay J.H. Taylor, Ted Ray and Harry Vardon, with Sandy Herd and Harold Hilton just a few shots further back and James Braid a few more. Those six names would eventually account for 20 Open Championships and 102 top-10s.

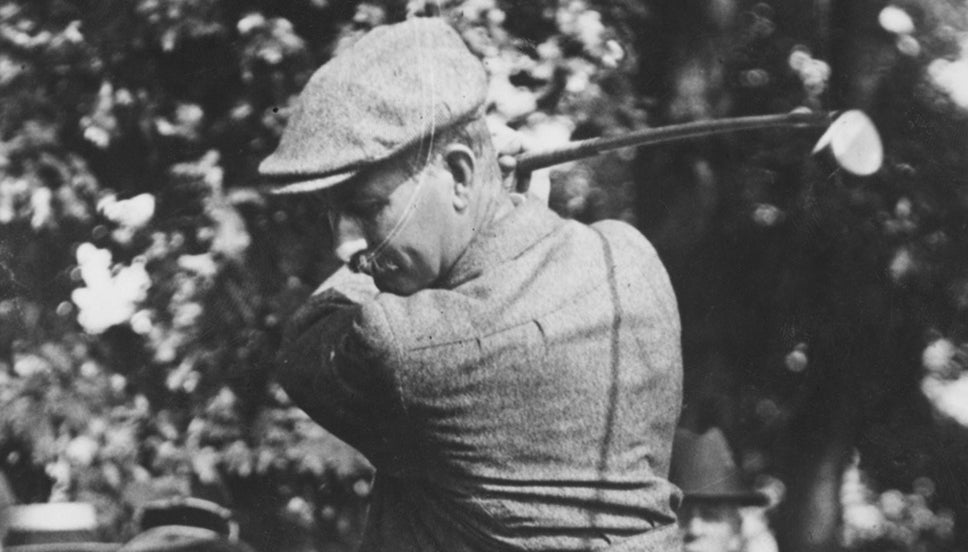

Of that list, it was Vardon who shone brightest in round three. Newspaper columns waxed lyrical about Vardon's play in round one, where he did not miss a putt inside of eight feet, but it was on Thursday morning when he truly made his mark on The 51st Open. A 75 in round three was significantly better than his nearest rivals, and gave him an outright lead of three strokes.

Still, 75 was not an overly impressive round on an odd, still morning where scores were unusually high. Thus, alongside Duncan's regression with an 83, a tantalising final round awaited should Vardon not be on top form, with stars lying in wait.

A final round of great drama

The Mail deemed Thursday as a day "quite unparalleled in the history of The Open", with the majority of golf's greatest players all competing for The 51st Open. They elaborated that, "exciting as had been the play in the morning, it was positively dull compared with that of the afternoon."

In the early 1900s, golfing fans were used to Open Championships, and most other matches, developing frequently into a two-horse race, with three contenders a more infrequent, if possible, occurrence. While the opposite of this is perhaps true today, The Open of 1911 certainly went in the face of tradition.

Still, the quality of golf was ever-growing, and the number of golfers who could be considered a threat at The Open was increasing year-upon-year. So it proved at Royal St George's, where no fewer than eight players could have claimed the Claret Jug, and as The Mail reported, "nearly every one of them at one time seemed likely to do so."

Vardon, after surprisingly reaching the turn in a less than stellar 38, "proceeded to hurl away his chances in the most lamentable manner" in the words of The Mail, taking 6, 5, 5 to start the back nine. He managed to shoot 80 in the end, and as he teed off earliest of all, his competitors knew that 303 strokes was their 72-hole target to beat.

Harold Hilton seemed in a superb position to win his third Open after a brilliant front nine of 33. As it turned out, a back nine of just 41 would have been enough to win outright, but the amateur limped home in 43, eventually finishing with two straight fives to fall just one behind Vardon with 304 strokes for the four rounds. It was a day that was opposite to the Hoylake man's usually stellar final round performances.

Other members of The Great Triumvirate were charging too. The Triumvirate was indeed dubbed 'The Great Quartet' at the time, with Sandy Herd's name thrown into the mix. Although Herd had only one Open title to his credit, a fact that eventually left him out of history's Great Triumvirate, his perennial contention was a given in The Open, and he was considered a player in the same breath as Vardon, Braid and Taylor.

This was no different in 1911, and Herd found himself with a nine-foot putt on the 18th to tie Vardon for the clubhouse lead, out in the early part of the final round. But in an agonizing twist, Herd's ball hopped in and out of the hole, leaving him with a 304 total and in a share of third with Hilton.

In fact, all four members of the then 'Quartet' finished in the top five of The 51st Open. Braid, after his inauspicious beginning on Monday, recovered well before taking 78 in his final round to miss out by two strokes, and Taylor's 79 also offered a case of what might have been.

Ted Ray made a charge to start his back nine, but fell back to a 305 total alongside Braid and Taylor. Duncan, the 36-hole leader, also had a chance in the afternoon, but eventually finished three strokes back on 306.

The only player to tie Vardon all day was the Frenchman Arnaud Massy. Massy had shown fine form in the build-up to the Championship, shooting a 72 around Sandwich in the practice days, and was undoubtedly one of the favourites for the title.

Needing to take just 12 strokes on his last three holes to finish level with The Stylist, the galleries excitedly watched on as he did just that, and voraciously cheered as he succeeded where others failed, taking The 51st Open into a play-off.

The play-off

In April of 1908, Vardon beat Massy, the then-reigning Champion Golfer of the Year, in a match held at Royal Cinque Ports. Just three years later, the pair rekindled their rivalry across the dunes at Royal St George's in The Open.

In 1907, Massy had become the first ever victor of the Claret Jug from outside of Britain, and Vardon's victory over him in their 1908 match at Deal was a victory for the wounded pride of British golf fans as much as it was for Vardon.

Still, the charismatic Frenchman Massy had already proven his significant golfing ability to the world, and had won a great measure of respect from crowds by the time the more significant circumstances of The 51st Open arrived.

Vardon, however, had play-off history, competing 15 years previously in the most recent occasion where extra holes were required in the Championship, an Open that also happened to be his first.

That experience showed, and it became quickly apparent that Vardon was in an ominous mood. Both players went out in excellent scores of 36, delighting the galleries, before Vardon pulled ahead on the back nine of the first round. A disastrous seven at the 17th for Massy compounded his problems, and Vardon took a five-stroke lead on to the second loop of 18.

The excellent golf continued from Vardon, before on the 35th of 36-holes the Championship was decided. Massy found trouble off the tee, and down by 10 strokes, conceded the title to Vardon in a gracious act that drew rapturous applause for both players.

It was The Stylist's fifth Championship victory, tying him with James Braid for the most ever, and put him in the most elevated company. A sixth Open would follow three years later, and to this day Vardon remains the most prolific player ever in The Open. His victory in 1911, however, surely took the longest, and was the most eventful of all of his six triumphs.